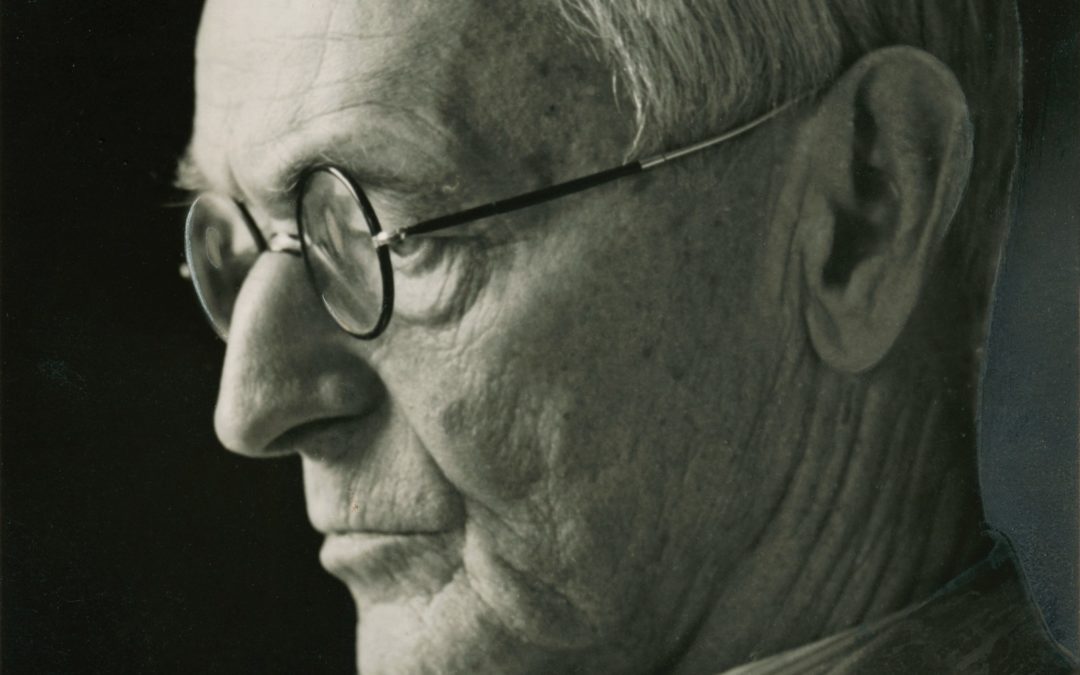

It was time to circle back once again to one of my favorite novelists, Hermann Hesse.

Hesse was a seeker of the truth. The quest to uncover and realize one’s essential nature was his driving motivation and, naturally, that of the protagonist of every novel from (at least) Demian on. This motive’s attraction for me has only grown deeper over time, with repeated reading.

My favorite novels of his are Demian, Narziss and Goldmund and The Glass Bead Game.

Demian recalls an unforgettable period of my life, my mid-20s, when I belonged to a philosophical school which teachings, while being incomplete, were nonetheless a great benefit. I read some amazing books in those days… The personal association was also a joy.

The duality of the titular characters Narziss and Goldmund has always been compelling reading for me, though I don’t believe Hesse has the final word on the subject: that duality does resolve, when we understand our essential, spiritual nature. That said, those two characters are just unforgettable.

The Glass Bead Game, Hesse’s final novel and generally accepted as his masterpiece, is a tour-de-force of fictional biography and a deeper meditation on the inescapable dualities of life in the material world.

While I wouldn’t approach Hesse looking for a spiritual teacher, he is absolutely a kindred spirit when it comes to artistic ethos. Witness this passage from Narziss and Goldmund:

… at his St. John, whose cherished, pensive features came to meet him out of the wood with greater and greater purity, he worked only during hours of readiness, with devotion and humility…

This, Goldmund sometimes felt with a shudder, was the way true art came about. This was how the master’s unforgettable madonna had been made, which he had visited in the cloister again and again on many a Sunday. The few good pieces among the old statues which were standing upstairs in the master’s foyer had come into being in this secret, sacred manner. And one day that other, the unique image, the one that was even more hidden and venerable to him, the mother of men, would come about in the same manner. Ah, if only the hand of man could create such works of art, such holy, essential images, untainted by will or vanity. But it was not that way. Other images were created: pretty, delightful things, made with great mastery, the joy of art lovers, the ornament of churches and town halls – beautiful things certainly, but not sacred, not true images of the soul. He knew many such works, not only by Niklaus and other masters – works that, in spite of their delicacy and craftsmanship, were nothing but playthings. To his shame and sorrow he had already felt that in his own heart, had felt in his hands how an artist can put such pretty things in the world, out of delight in his own skill, out of ambition and dissipation.

When he realized this for the first time, he grew deathly sad. Ah, it was not worth being an artist in order to make little angel figures and similar frivolities, no matter how beautiful. Perhaps the others, the artisans, the burghers, those calm, satisfied souls might find it worthwhile, but not he. To him, art and craftsmanship were worthless unless they burned like the sun and had the power of storms. He had no use for anything that brought only comfort, pleasantness, only small joys. He was searching for other things. A dainty crown for a madonna, fashioned like lacework and beautifully gold-leafed, was no task for him, no matter how well paid. Why did Master Niklaus accept all these orders? Why did he have two assistants? Why did he listen for hours to those senators and prelates who ordered a pulpit or a portal from him with their measuring sticks in their hands? He had two reasons, two shabby reasons: he wanted to be a famous artist flooded with commissions, and he wanted to pile up money, not for any great achievement or pleasure but for his daughter, who had long since become a rich girl, money for her dowry, for lace collars and brocade gowns and a walnut conjugal bed with precious covers and linens…

Hesse, Hermann, 1930. Narziss und Goldmund,

trans. Ursule Molinaro as Narcissus and Goldmund. New York: Picador, 2003.

Hesse understood artistic creation as a spiritual calling, a healing process of discovery. Any material results of that work are so much after the fact as to be irrelevant to him, and making those results his goal and his work’s purpose would be unthinkable. That can be left to the rank materialists whose one-dimensional, cookie-cutter product litters an ever-degrading popular culture.